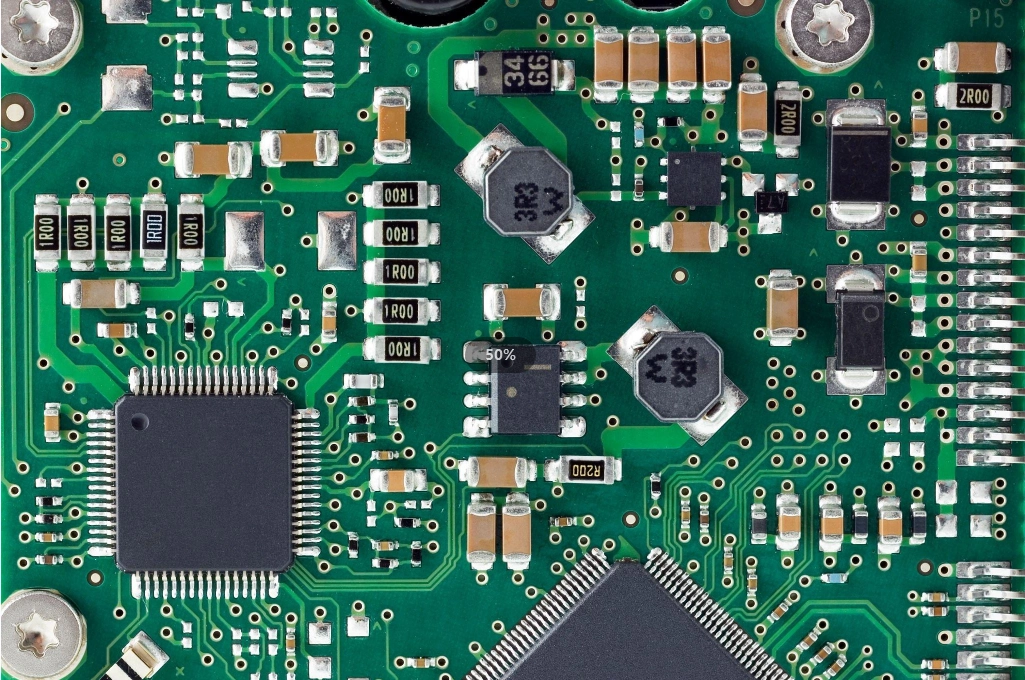

When putting together modern electronics, manufacturers use different soldering methods like wave soldering, reflow, vapor-phase, and selective soldering. The components can be anything from classic through-hole parts to advanced packages like surface-mount, BGA, micro-BGA, CSP, stacked packages, or even chip-on-board (COB). Because today’s devices are so small and packed with parts, you often see system-in-a-package (SiP), which combines multiple chips into one package, or system-on-a-chip (SoC), where everything is integrated onto a single chip. These advanced package types make the assembly process a lot more complex. For example, you might need adhesives for parts on the underside of the board, underfill for CSPs, wire bonding and encapsulation for COBs, and different kinds of solder paste or flux depending on the job.

When you’re building complex printed wiring assemblies (PWAs), the heating process has to be carefully chosen. You need to think about things like the size and weight of the assembly, how tightly packed the components are, the type of solder paste or flux being used, and how much heat the parts can actually handle. Most components can only withstand about 240 °C with traditional tin-lead solder. The problem is, some components—like electrolytic capacitors or plastic-encased parts—can’t survive the higher temperatures needed for lead-free soldering. Too much heat can cause them to degrade, which may lead to early failures in the field.

This is especially tricky for optoelectronic parts. They’re very sensitive to heat, and the higher lead-free processing temperatures can cause all sorts of issues: electrical shifts, changes in silver-epoxy die bonds, delamination between plastic and metal, warping of plastic housings or lenses, damage to coatings, and even changes in how much light passes through.